Whatever may be the plan resolved upon, I ardently hope it will be alike calculated to reflect honour upon the bard and upon the country. Let the celebration be worthy of the man, to whom England is more indebted than to any name her annals can boast. I allude not to his poetry alone, wonderful and unrivalled though it be it is clear to me that the manly love of freedom, and vigour of thought peculiar to Englishmen, has arisen in no small degree from the general circulation and perusal of his plays.

Theatrical Inquisitor and Monthly Mirror, April 1816, p.266.

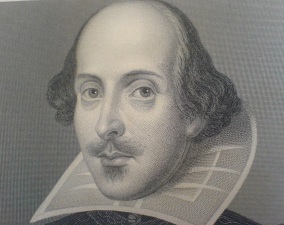

Shakespeare, by Droeshout, reproduced in The Illustrated Library Shakspeare (London: W. Mackenzie), IX. Image from PUNCS collection.

Shakespeare, by Droeshout, reproduced in The Illustrated Library Shakspeare (London: W. Mackenzie), IX. Image from PUNCS collection.

So commented the correspondent ‘R.T.’, in a letter to The Theatrical Inquisitor, a periodical published in London, in 12 April 1816.

Romanticists, Gothicists, Victorianists and others have written much about the nineteenth-century’s response to Shakespeare: on stage, in literature, music and in the visual arts. We have had – to list just modern works – Adrian Poole’s Shakespeare and the Victorians (2014); Joseph Ortiz’s edited collection Shakespeare and the Culture of Romanticism (2013); Stuart Sillars’ Shakespeare and the Victorians (2013) and Shakespeare, Time and the Victorians: A Pictorial Exploration (2011); Gail Marshall’s edited collection Shakespeare in the Nineteenth Century (2012); Kathryn Prince’s Shakespeare in the Victorian Periodicals (2011); Kimberley Rhodes’s Ophelia and Victorian Visual Culture: Representing Body Politics in the Nineteenth Century (2008); Andrew Murphy’s Shakespeare for the People: Working Class Readers, 1800–1900 (2008); Richard Foulkes’s Performing Shakespeare in the Age of Empire (2006); Richard Schoch’s Not Shakespeare: Bardolatry and Burlesque in the Nineteenth Century (2003); Linda Rozmovits’s Shakespeare and the politics of culture in late Victorian England (1998); Schoch’s Shakespeare’s Victorian Stage: Performing History in the (1998), Valerie Gager’s Shakespeare and Dickens: The Dynamics of Influence (1996) … and essays by many other scholars! The most recent collections include, appropriately for a blog published in April 2016, Christa Jansohn and Dieter Mehl’s edited collection, Shakespeare Jubilees: 1769–2014 (2015).

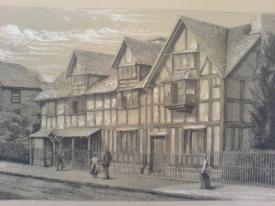

Shakespeare’s House, from The Illustrated Library Shakspeare, IX

This blog essay looks at the treatment of Shakespeare during the two hundredth anniversary of his death. Adrian Poole has recently (in Clara Calvo and Coppelia Kahn’s edited collection, Celebrating Shakespeare: Commemoration and Cultural Memory, 2015) explained why 1816 saw so little in the way of Shakespeare commemorations in Britain: there being other concerns, after the defeat of Napoleon in the previous year, and the economic consequences of the end of global war. Poole’s essay, ‘Relic, pageant, sunken wrack: Shakespeare in 1816,’ studies the commemorative activities of the antiquarian John Britton (promoting the sculptured likeness in Stratford church as the only authentic image of the bard, via William Ward’s mezzotint … from an oil painting by Thomas Phillips … after a cast by George Bullock …. from the monumental bust), the essayist William Hazlitt, and the novelist Sir Walter Scott, whose works, Poole notes, have Shakespearian phrases scattered throughout them.

Britton’s print was to be sold for £1 on Indian paper in proof stage, the plain quarto edition for subscribers would be 10s. Britton published an accompanying Remarks on the Monumental Bust of Shakspeare, at Stratford-upon-Avon: with two Wood-cuts, representing Front and Profile Views of the Bust.— London; published by the Author, April 28, 1816. To accompany a Portrait engraved by William Ward, A.R.A. from a Picture, by Thomas Philips, Esq. R.A. and wrote to the press (e.g., European Magazine, July 1816, pp.32-34).

Various engravings have indeed appeared, purporting to give exact representations of the Bust, but most of those are executed in the vilest manner, and none are perfectly correct copies. The admirers of Shakspeare are therefore deeply indebted to Mr. Britton for the admirable engraving which the Essay before us is intended to illustrate; it was executed under his immediate inspection, and is a most perfect resemblance of the original. The ‘Essay,’ and ‘Portrait’ were delivered to the subscribers on the 23d of April last, the day which completed the second centenary of years from the poet’s death. In a pecuniary point of view Mr. Britton will not probably have much reason to felicitate himself on the task he has performed; but he has deserved and will receive the thanks and gratitude of all those, whose admiration of the poet of nature is as enthusiastic and glowing as his own.

The Theatrical Inquisitor, vol. 9, July 1816, p.50.

‘Shakspeare’s Monument’, The Illustrated Library Shakspeare, IX

What of other commemorative efforts beyond these individuals, and beyond the damp event of the ‘Grand Pageant’ – with its ‘pantomimic representation of the principal scene’ in selected plays and it commemorative medal – that occurred at Stratford-on-Avon on Tuesday 23 April 1816, and which itself initiated the tradition of anniversary celebrations?

COMMEMORATION OF SHAKSPEARE.

THERE will be a PUBLIC BREAKFAST

at Shakpeare’s Hall, Stratford-upon-Avon, on

Tuesday the 23d of April instant, at Ten o’clock;

at Four o’clock precisely there will be a DINNER;

and in the evening a BALL. Dancing to commence

at Ten. –

STEWARDS.

Right Hon. the Earl of GUILDFORD.

Right Hon. Lord MIDDLETON.

Sir CHARLES MORDAUNT, Bart. MP

FRANCIS CANNING, Esquire.

Tickets for the Dinner will he delivered at the Bar

of the Red Horse Inn, and at Mr. Ward’s, stationer,

Stratford; and, those Gentlemen who purpose ho-

-nouring the company with their attendance, are most

particularly requested to send for Tickets on or before the I9th instant, in order that a suitable provision may be made.

Tickets for the Breakfast and Ball to be had also of Mr. Ward.

Oxford Journal, 13 April 1816

[Mr Ward was the bookseller and stationer James Ward, who published R.B. Wheler’s Historical and Descriptive Account of the Birth Place of Shakespeare, 1824]

The metropolitan theatres had their commemorations. At Drury Lane, after a performance of Romeo and Juliet; and at Covent Garden after a performance of Coriolanus, actors recited David Garrick’s Jubilee Ode of 1769 and performed the Stratford Jubilee. The Evening Mail and London Courier, 24 April, described this work as ‘trifling and nonsensical’: extracting the following gems from Garrick’s verse, ‘The Warwickshire Lad’:

Ye Warwickshire lads and ye lasses,

See what at our jubilee passes;

Come revel away, rejoice, and be glad,

the lad of all lads was Warwickshire lad.

Warwickshire lad,

All be glad,

For the lad of all lads was a Warwickshire lad.

The actor Pope’s recitation at Drury Lane was said to resemble ‘that of a Methodist parson somewhat muddled with porter’ (Theatrical Inquisitor, p.373). At Covent Garden, Charles Kemble’s cast (which included ‘Master Betty’ as Hamlet) ‘gave, in dumb shew, little characteristic touches, which were much admired by the audience, who were thus happily reminded of many of the most striking scenes in their favourite Author’s works’ (Morning Post, 24 April 1816). There was also Banquo’s ghost, the witches’ cauldron, the tomb of the Capulets and other appropriate stage ‘machinery,’ with the image of Shakespeare ‘wearing his immortal wreath.’ Songs, Chorusses, &c., in the Musical Afterpiece, Called Garrick’s Jubilee: As First Performed at the Theatre-Royal, Drury-Lane, in 1769, and Now Revived, (under the Direction of Mr. Farley), at the Theatre-Royal, Covent-Garden, 23d of April, 1816, Being the Second Centenary of Years from the Death of Shakspeare … with a Plan of the Grand Pageant of the Characters of Shakspeare, by the Whole of the Company, to give its full title, was a sixteen-page pamphlet published by John Miller.

Detail from engraving of Coriolanus, after Sir John Gilbert, The Illustrated Library Shakspeare, V.

The metropolitan and Stratford-upon-Avon celebrations were reported in the provincial press across Britain. There were some provincial commemorations too – though these were limited. At Newcastle-upon-Tyne, it was announced that Garrick’s Jubilee would also be performed at the Theatre Royal, then being managed by the actor William Macready. The theatrical entertainment followed a public dinner at the Queen’s Head Inn (Durham County Advertiser, 13 April 1816). The note was signed by the printer and bookseller Edward Humble (1753–1820). Humble was secretary to a committee of the theatre proprietors and also proprietor of the Shakespeare Press (and Durham County Advertiser) in Newcastle. Afterwards, this newspaper – an ‘ultra Tory’ paper – reported that seventy gentlemen had been present: these included the mayor of Newcastle, Colonel Ramsay of the Artillery, and as the chairman, the banker and son of a baronet, William Loraine (1780–1851). Apart from toasting the memory of the immortal bard there were toasts to the royal family, Princess Charlotte and her husband-to-be; the Duke of Wellington; and even Sir Humphry Davy ‘who by a late ingenious invention, had rendered such services to this neighbourhood’). Shakespeare, Loraine declared, had raised ‘the British stage to such a pitch, as not only to become a source of national pride to his country, but the admiration and the envy of surrounding nations’ (Durham County Advertiser, 27 April 1816).

The semi-retired actor and manager Stephen Kemble (1758–1822), who spoke at the dinner, inevitably [mis]quoted Shakespeare’s John of Gaunt: ‘this land, this dear, dear land, this precious stone set in the silver sea’. The Theatre Royal entertainment included Twelfth Night with Garrick’s Jubilee, but also George Colman the younger’s Sylvester Daggerwood (or, New hay at the old market: an interlude, in one act)… The landlord Peter Forster’s decorations at the Queen’s Head hotel included a ‘colossal figure of Shakespeare resting on a pedestal, and holding in his hand a scroll, on which were inscribed the beautiful lines, beginning “the cloud-cap’t towers, &c.” graced the room, and had a pleasing effect.’ Evidently this was a copy of the monument in Westminster Abbey by William Kent (1740), with the same quotation from The Tempest. The commemoration was reported in the pages of The Theatrical Inquisitor (May 1816, pp.333-334).

There was commemoration further afield: the Caledonian Mercury (4 May 1816) reported:

In no part of his native country could the anniversary of this great man have been celebrated with higher devotion and enthusiasm, than at Alloa, in Clackmannanshire. A Shakespeare Club has for many years existed in that place, the members of which have always held a literary festival on the day that gave birth to the greatest poet the world ever beheld … a number of their literary friends and acquaintances were invited to join in the social pleasures of the evening. When dinner was over, and a few general toasts were given, the President rose, and after an appropriate eulogy, concluding with a quotation from one of the poet’s best plays, gave, ‘The memory of Shakespeare,’ which was drunk standing, and in deep silence. Mr James Hogg, the Ettrick Shepherd, who is now an honorary member, and poet laureate of the Club, then produced and read an ode ‘To the genius of Shakespeare;’ upon which the president, after a short address most flattering to the bard, and well calculated to encourage him in his poetical career, presented him in name of the Society, with a handsome silver cup, having the Shakespeare arms beautifully engraved on one side, and the following inscription on the other, ‘Presented to Mr James Hogg, by his brethren of the Shakespeare Club of Alloa in testimony of their esteem for him as a man, and their admiration of him as a poet.’

Hogg’s poem, probably the same as that published in his collected works, began:

To The Genius of Shakespeare

Spirit all limitless,

Where is thy dwelling-place?

Spirit of him whose high name we revere,

Come on thy seraph wings,

Come from thy wanderings,

And smile on thy votaries, who sigh for thee here!

Come, O thou spark divine!

Rise from thy hallowed shrine!

Here in the windings of Forth thou shalt see

Hearts true to Nature’s call,

Spirits congenial,

Proud of their country, yet bowing to thee!

The Poetical Works of the Ettrick Shepherd: Including the Queen’s Wake, Pilgrims of the Sun, Mador of the Moor, Mountain Bard, Etc., Etc. With an Autobiography, and Illustrative Engravings, from Original Drawings, vol. 4 (Glasgow: Blackie, 1840).

This event, too, was reported in the pages of the Theatrical Inquisitor, which had sought ‘accounts of the various celebrations of the second centenary of the immortal Shakspeare’.

If Scotsmen such as James Hogg of Ettrick (1770–1835) and his associates (the club being founded by the timber merchant Alexander Bald in 1804, see The Collected Letters of James Hogg: 1800–1819, 2004, p.443) at the town and port of Alloa in the Scottish Lowlands could embrace Shakespeare as a native genius, what of Stratfordians who might be expected to especially cherish the memory? They had been asked (through a letter in Worcester Journal, 18 April 1816), as Englishmen and townsmen, to ‘rejoice in the natal honour of our illustrious poet,’ and to ‘endeavour to fully appreciate his worth, prove that the world, and implant it on the plastic mind of the rising generation … Though our creeds properly forbid us to worship his name or image, yet we may revere the one, admire the other, and continue to peruse his works with infinite gratification and advantage.’ (‘R.B.W.’ – the historian R.B. Wheler).

Not everyone was an admirer and the Theatrical Inquisitor had reprinted the radical William Cobbett’s attack on bardolatry (in the course of a diatribe against ‘the Potato’) in 1816:

I ask you what it is that can make a nation admire Shakspeare? what is that can make them call him a ‘Divine Bard,’ nine tenths of whose works are made up of such trash as no decent man, now-a-days, would not be ashamed, and even afraid, to put his name to? what can make an audience in London sit and hear, and even applaud, under the name of Shakspeare, what they would hiss off the stage in a moment, if it came forth under any other name? When folly has once given the fashion she is a very persevering dame.

Theatrical Inquisitor, February 1816, p.94.

The patriotic strain is noticeable in newspaper commentary elsewhere: the Chester Chronicle commemorating the 23 April, on 3 May, with a paragraph which describes Shakespeare as ‘This Divine Poet’ and the ‘Pride of Britain, of poetry, and the Drama’. Later came news, as reported in the Gentleman’s Magazine (April 1816, p.349; and reprinted in provincial papers such as Manchester Times), of the honour given by the Académie Française to the poet Jean-François Ducis (1733–1816), who had died in March: ‘England especially may view with pleasure the distinction shown to a man devoted to English literature, and who, his six translation, from Shakespeare, … manifested at least his fond admiration for the great Bard, whom the mass of Frenchmen, not having the capacity to comprehend, presume in their ignorant vanity to despise.’ (But see John Pemble’s Shakespeare Goes to Paris, 2006).

1816 had seen a pantomime-tragique put on by Bonnachon in Paris, based rather distantly on Hamlet, in which the ghost came to life as a talking statue at the end of the play (see Helen Bailey, Hamlet in France: From Voltaire to Laforgue, 1964, p.26). Lady Morgan’s La France en 1816 (vol.2, pp.125-126), has an extensive footnote on the French lack of knowledge of Shakespeare, through Voltaire’s bad translations. Yet the Theatrical Inquisitor suggested that English tastes were being catered for – Paris being ‘full’ of them in early 1816 – with performances of Hamlet and Alexandre Duval’s afterpiece in one act, ‘Shakspeare Amoureux, ou La Pièce a l’Étude’ at the Académie Royale de Musique in the Rue de Richelieu. (Theatrical Inquisitor, January 1816, p.48). Shakespeare in love was played by the actor Francois-Joseph Talma.

‘Sigh no More Ladies’, from Much ado About Nothing, Act II, Scene III. By Sir John Gilbert, Illustrated Library Shakspeare

In Prussia, by contrast, a serious production of Hamlet was staged on 23 April 1816 at the Berlin Royal Theatre (see Christine Roger’s La réception de Shakespeare en Allemagne de 1815 à 1850: propagation et assimilation de la référence étrangère, 2008). A Dane, Jorgen Jorgenson wrote, in Travels through France and Germany, in the Years 1815, 1816, & 1817 (1817) that ‘Shakespeare’s plays are exhibited here with much éclat, and in their true senses’. Shakespeare’s work had been translated, adapted and were starting to be performed in Scandinavia in the early-nineteenth century, a commemorative performance of Shakespeare apparently took place in ‘Hamlet’s castle’ of Kronborg in Denmark, for instance, in 1816 (for the translation of Shakespeare in Europe in this period, see Dirk Delabastita and Lieven D’hulst, eds, European Shakespeares: Translating Shakespeare in the Romantic Age, 1993; see also Jozef de Vos and Paul Franssen, eds, Shakespeare and European Politics, 2008 for essays which explore the impact of versions of Shakespeare elsewhere in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Europe, for example, in Spain).

Images of King Lear by Sir John Gilbert, the Ghost in Hamlet by Robert Dudley, and ‘Come Away Death’, Twelfth Night, Act II, Scene II, by Sir John Gilbert: all from The Illustrated Library Shakspeare