Image: Punch, 31 December 1859: image in PUNCS collection

One enduring item in the British culinary self-imagination has been the plum pudding – often closely associated in festivities with the roast beef (of old England). The pudding – so named for the dried fruits which may have included fruit other than prunes – was not just for Christmas time but has come to be associated with this festival: and this short essay traces its visual representation and uses over the ‘long nineteenth century’. The dish can be traced back to the medieval dishes of spiced, meat and fruit flavoured broths and porridges; and, although in our calorie-conscious modern age we might not like to eat it ourselves, it was a prized dish in English history.

Thomas Rowlandson, the famous graphic artist of the late eighteenth century, chose the sight of a pudding glimpsed through a window (held by a puddingey-looking figure), to illustrate the passion of ‘admiration’ – in this case it is really the hunger of a youth for a ‘Plumb Pudding’ – in a series of engravings in 1800.

The graphic artist Isaac Cruikshank, in 1807, depicting one of the Christmas customs of ‘Twelfth Night’ (which had its own cake), has that famous embodiment of national identity, the corpulent John Bull, speak: ‘let things go on as they will – do not let us lose sight of Old English Customs – the Bulwarks of our Constitution’. Plum pudding could be seen in this light – an edible bulwark of the English Constitution.

The next image we might consider shows a depiction of the pudding being steamed, in an engraving designed by an artist, George Cruickshank, closely associated with the novelist Charles Dickens. Here the suetty fruit pudding is wrapped in cloth and being boiled in a ‘copper’. In Dickens’ A Christmas Carol (1843), Ebenezer Scrooge’s third spectral visitor, the ‘ghost of Christmas present,’ as drawn by John Leech, points to the now established motif of the spherical plum pudding adorned with holly – the ‘speckled cannon ball’.

The pudding is a hearty dish, full of fats (and with butter sauce to add) ideal for an era before central heating. But the dish as a source of indigestion figures in a number of nineteenth-century representations. An 1835 image, a humorous engraving by Alfred Crowquill, shows the devils of indigestion tormenting a man: a slice of Christmas pudding lies on the table beside the agonized fellow.

We can look up references to the plum pudding quite easily using internet-published material, using the digitised texts from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries freely available through Google books, and though searches of online sites such as Bridgeman Art Gallery. Image searches also reveal a mass of pudding-related imagery: from comic and sentimental imagery to more serious visual record engraved illustrations in nineteenth-century newspapers (where, as we shall see, the contrast between the ‘homely’ and the exotic and perilous, could be dramatized by the presence of the pudding), to chromolithographic (colour-printed) Christmas cards.

There’s a certain nostalgia for the early nineteenth-century ‘Merrie England’ of the Georgian Regency in some of the late-Victorian images, thus G.A. Storey’s serving maid with wooden ladle who is ready to offer the viewer to ‘Come stir the Christmas pudding’, in Illustrated London News, 9 December 1893; and Charles Green’s ‘Christmas Comes but Once a Year,’ which was a colour lithograph that appeared in Pears’ Christmas Annual in 1896 and which show a servant bringing the steaming pudding into a middle-class dining room. The Graphic’s Christmas number for 1873 went further back in the history of the pudding with its representation of a jester stealing a kiss from an encumbered Tudor serving wench in an image by Durand. Children stirring the Christmas pudding mix in the bowl (and making a wish) played to Victorian sentimental tastes, with prints offered in Christmas numbers of the illustrated press, with mother and maids in The Graphic in 1876, or alone, as in Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News in 1885 and, with (presumably) her mother, in the Illustrated London News in 1889.

From this overview of the pudding’s visual history, we can take the pudding’s life history from c.1781 through to the twentieth century interwar period. The first image we might look at in more detail is the representation of England in a series, ‘Seven Prints of the Tutelar saints’, published in London in 1781. Here we see the lion’s paw on which a Englishman is mounted like a horseman (the man is dressed like a sailor/soldier hybrid), rests on a bowl of pudding. The pose is an echo of the lion of St Mark, whose paw rests on a globe. The verse printed below, speaks of ‘noble sirloin, rich pudding and strong Beer’.

The pudding figures in texts examining English character and manners, in the eighteenth-century. The foreign observer Henri Misson commented, in a text published in 1719, on the Englishman’s joys at ‘pudding time’ – a native phrase which meant to arrive opportunely. The English treated it like manna from heaven, Misson wrote, ‘Ah, what an excellent thing is an English pudding. To come in pudding time, is as much to say, to come in the most lucky Moment in the world.’ An English writer’s riposte to this satire, in The Freeholder, 2 April 1716, was that the dish, ‘it must be confessed is not so elegant a dish as frog and salad’, thus responding in kind by expressing those prejudices about the oddities of Gallic cuisine. As a symbol of all that was stodgy about the unreformed English polity, John Cannon, in his study, Parliamentary Reform 1640-1832 (1973), describes the eighteenth-century as ‘Pudding Time’ (in this case, quoting from verse entitled, ‘The Vicar of Bray’). Plate 6 of George Cruikshank’s Illustrations of Time, of 1827, has the pudding being presented at the dining table to illustrate the idea of ‘Pudding Time’.

Let’s consider next the famous representation, by the leading graphic artist of the late-nineteenth-century, James Gillray, immortalising prime minister, William Pitt the Younger as the partner in a meal-for-two on a global scale: carving up the globe with that arch-enemy of the British empire, Napoleon Bonaparte. The image: reproduced as an etching published on 26 February 1805 (by H. Humphrey of 27 St James’s Street) has the caption:

‘The Plumb-pudding in danger: –or –State Epicures taking un Petit Souper’

‘the great Globe itself, and all which it inherit’, is too small to satisfy such insatiable appetite’

[you can see this in the high resolution image in Wikipedia]

It is quite a sparse cartoon for Gillray – and all the more effective for this. The context, according to the scholarly commentary, is the attempt to broker peace with Britain, on the part of the new Emperor, in January 1805. But we might also contextualise the image in Gillray’s frequent use of food and eating, in such cartoons as ‘John Bull taking a Luncheon – or – British Cooks cramming Old Grumble-Gizaard with Bonne Chere’; and the grisly ‘Un petit Super à la Parisienne: –or – A Family of sans Culotts [sic] refreshing after the fatigues of the day’: which links the French revolutionary terror with cannibalism. You can see the image ‘The Plumb-pudding in danger’ in the online collection of the National Portrait Gallery. If you search Google images, you will find evidence for the continued influence of this striking image in a cartoon by Dave Brown, The Independent, from 2011: carving up Libya and causing an oil fountain to explode. Nineteenth-century homages to this image appear in cartoons by British, American and continental European artists. But before this image had most memorably associated William Pitt with the plum pudding, there was ‘Plum Pudding Billy in all his Glory’. The image, which is a satire on Sir Watkin Lewis, the ‘child’ Pitt, and John Wilkes – on the occasion that the new Prime Minister was dined by the Lord Mayor and City of London figures, is explained by the script underneath:

The Chancellor Billy behold here is seated

To tast a plum-pudding by Sir Watty intreated.

He sticks on a leake more his fancy to please

And in hope of preferment is down on his knees

Squinting Jack as the C —-n comes in behind

Supposing he may want to S – t when he has dined

He holds the utencil & thinks not disgrace –

Lord how Folks are worshipd in Power and place.

The image is discussed in Anja Müller’s, Framing Childhood in Eighteenth-century English Periodicals and Prints, 1689-1789.

To return to the theme of French and British tastes, in a later cartoon, for the Illustrated London News, 21 December 1850, there appeared ‘The Dreadful Turn-out of a French Plum-Pudding!!! Or, the Misfortunes of Monsieur and Madame De La Betise, whose Grand Object in Life was to live in the English Style, trustfully narrated by Horace Mayhew and Alfred Crowquill’. This involves a disaster with the national dish (poudin aux raisins). The same sense of incomprehension plays out in a cartoon by A. Forestier, ‘An English Christmas in Paris. But is this Pudding? … Never Again’, in the same paper, in 22 December 1883.

As Maggie Black has argued, the enduring place of the plum pudding at Christmas time may be linked to the royal family’s support for the Christmas Day pudding ritual. Recipes appear in famous Victorian cookery books such as that book written – or at least assembled – by Mrs Beeton (1861).

As we have already seen, images abound in the Christmas-time issues of the illustrated periodicals and newspapers that emerged in the Victorian era. There was Kenny Meadows’ ‘pudding making’ and ‘pudding taking’ in the Christmas supplement to the Illustrated London News in 1848. On 23 December 1852 in the Illustrated London News we have ‘Plum-Pudding, a Dream of Christmas’, a story from Watts Phillips. In pantomime, such as the figures from a ‘Twelfth Night’ tale appearing in the Illustrated London News, we can also find plenty of images of the Christmas Pudding.

Plum puddings were celebratory and festive fare at Christmas. They figured as a demonstration of festive philanthropy for a society without the welfare state: with images of ‘pudding philanthropy’ in workhouses and other sites for the poor and the unfortunate. Thus members of the United Cooks’ Society are shown ‘preparing a Monster Plum-Pudding at Marylebone Workhouse for the Lancashire Operatives’, in a picture for The Illustrated London News, 3 January 1863. The recipients were the workers enduring hardship as a result of the crisis in the cotton textile industry. And, supposedly heart-warming and amusing, is the imagery for an item, published in The Graphic, 25 December 1886, by Harry Hamilton Johnston, the page depicts scenes from ‘A Christmas Dinner given by Actors to Poor Children in Lambeth’: we can also see the ‘Effects of the Pudding’.

The pudding also appeared in imagery outside Christmas, for example, during royal jubilees. The image entitled ‘The King and Queen at the Windsor Festivities’, published in The Graphic, 23 April 1887, was a late-Victorian visual recreation of a moment during George III’s Jubilee. The plum pudding might also appear outside any festivity: in parliamentary debates on the (protectionist) Corn Laws in April 1825 the fact that ‘the workmen London had roast beef and plum pudding on Saturday, Sunday, Monday, and Tuesday,’ was used in the debates in the Commons about agricultural interests vs. the interests of the rest of the country.

The politico-satirical use of the plum pudding which we have seen in James Gillray’s famous image, continued: see for example the nursery rhyme style vignette, ‘In the Thick of it, or a Regal Christmas Day’, by C.J. Grant, appearing in a newspaper from the 1840s. Here the royal couple (ALBERT: – Her, her, dis is von fine Blom Buddin, her, her; Angland is der Blace for goot tings.’) and the Duke of Wellington are shown helping themselves to a gargantuan plum pudding whilst handing over a plate of plum stones for an understandably disgruntled John Bull – represented as a cook, to eat. Florence Claxton (painter of the satire on the Pre-Raphaelites, ‘The Choice of Paris’, in 1860), imagined the reverse scene, in her bizarre ‘Utopian Christmas’, in the Christmas supplement to the Illustrated London News, 31 December 1859: the engraving showed Queen and Prince Albert overseeing the offering of pudding and other delights to the beggars and the poor, in Buckingham Palace.

There are foreign examples too, of the pudding used in political or social commentary at Christmas time: the American periodical Puck in December 1882, has a ‘Holiday Plum Pudding’ by J. Keppler, with a cherub, the knife engraved, ‘with malice towards none’ cutting through a pudding composed of the faces of celebrities of the day:

My final set of images to reflect, bring us back to the theme of the imperial pudding. Courtesy of The Graphic in 1878, we are in colonial India. In this coloured engraving: the European hunter offers a glass of alcohol to an obsequious native after a tiger hunt. A hamper is adorned with a small Christmas pudding. From the Illustrated London News, 8 February 1879, we have one scene from ‘Christmas at Jellalabad: The First Slice of the Plum Pudding’: the context is the war in Afghanistan. In The Graphic for 27 December 1879, there are dreams of the pudding and other traditional foods, for soldiers on the Afghan Campaign, ‘Christmas Tide at the Front’.

We can situate this image in a genre of the pudding delivered to grateful stomachs under, or after, peril. This vein of imagery continues in paintings such as W.H. Overend’s, ‘A Christmas Pudding for the Lighthouse,’ for the Illustrated London News in 1891; and ‘Christmas on the veldt: a correspondent’s pudding’, with the setting of the Anglo-Boer war, in The Sphere in December 1900. Linley Sambourne’s full-page cartoon from the Christmas number of the Illustrated London News for 1876 has a boy – asleep on animal skins and toy gun at his feet, dreaming a nightmarish pudding transmogrified into news items of African and Arctic expeditions (the theme of dreams related to plum pudding surface elsewhere, for example in Blanchard Jerrold’s The Story of Madge there is the angry housemaid who falls asleep, ‘scorning the Christmas pudding, despising the mince pies,’ but Fairy Content gives her a lesson in all the labour involved in making the plum pudding, The Athenaeum , 8 April 1871, p.431)

The pudding could and did travel. Captain Cook’s Voyages, as one cartoon image chromolithographed on a late-nineteenth century card recorded, had included the enthusiastic reception of plum-pudding by the friendly Lapps. In the late Victorian period, when commercially available puddings were advertised in the Illustrated London News, as manufactured by Peak, Frean and Co., the pudding could be sent abroad in tins. They could also be made by homesick settlers. W. Dalston’s image for the Illustrated London News, in 24 December 1870 shows white settlers tucking in to pudding in Australia. From the Graphic’s Christmas number in 1881, there appears a coloured sequence of images of two male settlers cooking and suffering the consequences of a pudding in Canada. There’s also an engraving, ‘Making a Christmas Pudding in China’, from 1873, showing Chinese men and youths looking on with interest as they are instructed by two British men, in the art of pudding stirring.

In the twentieth century, the pudding was literally the fruits of the empire, in the form of the Empire Marketing Board effort in 1828, which was endorsed by royalty – a pudding being presented to the King on Empire Day. There are several images of this campaign, ‘Making the Empire Christmas Pudding’, to sell the empire on the basis of all the exotic and not-so-exotic ingredients that were combined to make the English traditional delicacy and which allowed the British family to ingest, digest, incorporate, and assimilate the empire.

The imperial family was brought together through the pudding (John Mackenzie’s study Imperialism and Popular Culture uses this on the front cover), which also figured in an Empire Marketing Board film by Walter Creighton, ‘One Family … illustrating the food products supplied by Empire producers at Home and Overseas’ (there is a link to the film, below ). It could be made with Canadian apples, West Indian demerara sugar, Jamaican rum, English beer, cloves from Zanzibar, beef suet from New Zealand and spice from India. One advertisement for the Empire Xmas Pudding has Britannia in the role of pudding bearer, ‘and you will enjoy it all the more if you remember that, by using Empire fruit to make it, you give a helping hand to the thousands of British settlers Overseas…’ It is not surprising that the pudding has more recently been suggested as a lesson theme, to teach Key Stage pupils in England about the ‘vast range of the Empire’ and the role of women in the empire.

James Gregory, 21 December 2015

Further Reading

Blanchard Jerrold, The story of Madge and the fairy Content (London: J.C. Hotten, 1870)

Via Google books

Maggie Black, ‘The Englishman’s Plum Pudding’, History Today 31: 12 December 1981

http://www.historytoday.com/maggie-black/englishmans-plum-pudding

Web links

‘The Pudding King’, Ivan Day, in his Food History Jottings blog,

http://foodhistorjottings.blogspot.co.uk/2012_02_01_archive.html

Judith Flanders, ‘Victorian Christmas’, an essay published by the British Library,

http://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/victorian-christmas

https://janeaustensworld.wordpress.com/tag/christmas-plum-pudding/

http://www.victorianweb.org/mt/panto/6.html

What can we learn about the Empire from a Christmas pudding?

http://www.keystagehistory.co.uk/free-samples/the-empire-from-Christmas-pudding.html

‘One Family’

http://www.colonialfilm.org.uk/node/40

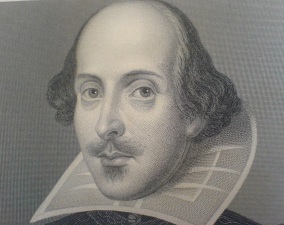

Shakespeare, by Droeshout, reproduced in The Illustrated Library Shakspeare (London: W. Mackenzie), IX. Image from PUNCS collection.

Shakespeare, by Droeshout, reproduced in The Illustrated Library Shakspeare (London: W. Mackenzie), IX. Image from PUNCS collection.